Was it Kierkegaard or Heidegger who said whiteness is a tennis court where the players never know within whose lines they’re playing while blackness is imprinted on the skin of the world’s negros by the heavy weight of a millennia of senseless nights. Whomever said it, it’s haunted me since; like a clear black ghost, rattling its black chains in the pitch-dark attic of the soul of my mind.

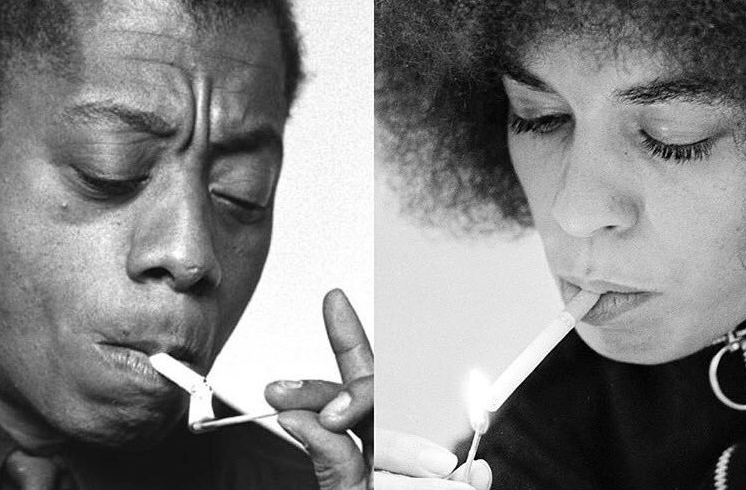

I drag in the smoke of my cigarette to remind me of death’s presence in my life. I had given up smoking in my twenties, but took it up again after Trayvon, Eric, Freddie, Sandra, Brianna, and Prince. I no longer want to be able to breathe well enough to run from the police. I want the deaths of their blackness to haunt my weary lungs like literal smoke, black smoke, black lungs, choking me and robbing me of the energy to live a life in which injustice is inescapable.

Or Xcapable. I know that it’s not a real word, but the skew of meaning that I give the word by branding it with the letter X provides this sweet black soul something to savor. And it’s the bitterness of our collective inability to understand language and meaning at all that I want to taste on my lips when I drag in my cigarette and sip at my macchiato. Not the salacious mahogany sweetness of the kind of macchiato you white people are used to, caramel dripping down the sides of an oversized cup, oversized of course, for it is the tendency of the white race to always drink from an oversized cup, taking more than their share, leaving only crumbs at the table, or spoiled cream, spilled from the empty half and half container, bags of raw sugar torn and emptied and the only sweetness left behind is that which clings to the stirring sticks they’ve thrown in the trash. And we of the black race must pull these sticks from the trash and lick them, suckle them, to have any sweetness at all, for a black man there is never any more vanilla syrup available for HIS latte, or coconut syrup, or raspberry syrup, for the black man it is only ever black coffee, and that is why I sip at my espresso in a tiny cup with only the smallest solace of a tiny dollop of burned and boiled cream floating limp on top like our bodies thrown from the ships by the slavers on their way to deliver us like so much sawn timber to the plantations of future America. Black America. My America. My prison.

It’s Xhausting. Even the caffeine can’t help, no matter how many macchiatos I put to my lips, there is no high, no coffee rush, for me there is only a sour and Sartre-like state of existential nausea. Which is what it must be, for blackness in America is itself the embodiment of Sartre’s nausea. Sicle-celled anemic and sick-stomached from hunger, or worse, overstuffed from the fleeting solace of soiled foods. Oiled and salted foods, foods meant to weigh down our black bodies and keep them from rising up against every oppressor. Foods meant to keep us from our natural state: foods meant to stop us from being a collective of Flo Jo’s, a nation of Carl Weathers, Barry Bonds’s free of bondage, Will Smith free of the chains of putty makeup the white man placed upon his perfect face when they forced him to play their sad approximation of our perfect Muhammad Ali born Cassius Clay.

My place, my state, the state I put myself in, is also nausea. But I go there willingly. I am not forced into pain by the white man, I take pain onto my body to remind the world of the ways of the white man. When you see me in the cafe smoking my e-cigarrette, surreptitIously, of course, hiding the minimal vapor trail, and sipping my coffee, squinting against the pain of oppression, you will know from the stack of books that I set beside me that this is a man who was born to carry the pain and memory of his people. Ibram X. Kendi, Ijeoma Oluo, W.E. Dubois, James Baldwin, Tony Morrison, TD Jakes, Trevor Noah, Ta Nehisi Coates, ?uestlove, Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Dr. Wayne Dyer. I carry their words everywhere I go, in hardcover. I want the weight of their life experience to add to the weight of my life’s toil. I want to carry them both with me and on me, and stack their works on every table I sit at to share their light with all passersby.

I may be black, but I do not believe that my dark soul cannot light up the world. Or let me think about that one again. I do not believe that there is no blackness in the light. Or that our dark does not preclude lamps. Let me try that again. I’m going to open up the Scrivener app on my iPad Pro so I can track changes if I want to use this later. Oh wait, listen to this one, I wrote it down last week: All that is light was born in blackness. That was good. Also this: The only way to take a picture of a black hole is to have a thousand cameras shudder at night. I like that too. It cools a hot face heated by the furnace of oppression.

Shudder is the proper word for the experience of blackness in this frozen world of newly gentrified Seattle that I have so recently moved my black body into through the purchase of a condo. The Seattle freeze is even colder than my studio in Brooklyn, or my parent’s colonial style home in Connecticut. Colonial. Colonizers. Colonization. It was a stifling place to be raised, Conneti-cut. All those ancient master’s homes and servant’s history, ever the taste of the master’s bit was in my young mouth, even before I had my “master’s” degree in European literature, even at horse camp as a child, always being forced to ride “English,” even on the debate team, always the token person of color, black color. There to jingle jangle with my black talk for the pleasure of my Asian brothers and South Asian sisters and strangely Portuguese teammates, who loved to comment on my “street” talk and “ghetto” style, though I, like them, had never experienced either, they assumed it born in me, and they branded me with it, like cattle, chattel. The white children of my youth constantly prodding me to join in their lacrosse games, as if sport was the only value my body had in the world. Their incessant cries of “I want Thaddeus on my team.” Thaddeus. My slave name. They claimed when I rejected them that their demands for my black body were compliments and not merely the entitlement they felt as white people. But I knew better. They only thought they were shouting “We Want Thad for Goalie!” What they were really shouting was “Jump N***** Jump!”

I am so tired. As of this last grey afternoon’s five hour writing session, my screenplay is a 1,000 pages and I still don’t have a sense of where it’s going or if it’s meant to go anywhere. What is life but meaninglessness? I set out to tell the story of all black people through the experience of one man’s life, my life, but so far I’ve only made it to the part where my mother’s family arrives on the Mayflower and my father’s ancestors are still 100 years from leaving Senegal for the West Indies. It might be another 1000 pages yet before my great grandmother sends her mixed race son to an all white Boarding School without telling him of the black blood beating in the freeways of his blue-black veins. I am beginning to think this is more of limited series than a film at this point, I had to upgrade my copy of Final Draft to keep working on it. The white man apparently doesn’t want all this truth in a mere two-hour feature. I’m thinking Amazon or Peacock might be my best bet, if not an independent production from A24.

But who can think? Really? Not me. I’m sick again from so much strong Ethiopian coffee and no food and I’m ready to leave the chains of this Starbucks. “There is only one truly serious problem in this world” Camus said. Did you know he was black too? An African heart beating in a French colonial body. Like Malcolm, Martin, and Webster, he also died early. The weight of his blackness too much to bear in a white world. Too much blackness for a white world to take. His blackness snuffed out like a candle, reversed. I worry my black fate may mirror his someday, an invisible sprectrum of darkness reflected back at my soul. My stomach aches at the chasm-ing emptiness.

I hope they have some day old scones at the counter.