Let’s begin with the first assumption. Yours. I’m not wheelchair bound. Bet you thought I was. We don’t use the term handicapped anymore, but we all know the sign, and on the sign it’s a guy in a wheelchair. And I’m not him.

That guy has a name. I bet you didn’t know that, either. Yep, the icon, the man in the chair, is a real man, who posed for a portrait that became the first ever produced and printed and distributed national handicapped parking sign. Fred Koeckne.

I bet you assume that he was some kind of activist. To be the icon, chosen for the image, destined to represent disabled people everywhere. The man responsible for for jacketing of every p-trap below every sink in every public bathroom in America. The first man to glide up a mild incline safely and easily into a building, instead of being battered backwards up a series of hard and unforgiving steps.

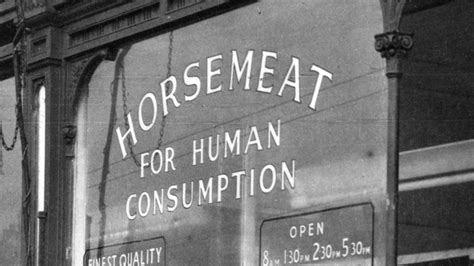

But Fred was not that man. He was no activist. Nor was Fred was disabled. See where your assumptions led you? Fred was a fully able-bodied man who had nothing to do with the campaign for disability rights. Fred was born in Brunswick, New Jersey in 1912, to an orphan father and an alcoholic mother. His family was desperately poor, and lived in a series of abandoned carriage homes vacated by the collapsing horse transportation industry. This was the time when the model T automobile was taking over New Jersey, and horses were being ground up for burger, having plummeted in value, and as you know, being expensive to feed.

Young Fred and his orphan father Charles worked as itinerant horse meat grinders right up until the Second World War. Now I bet you are thinking that I am about to say that Fred was called to fight in the Great War, and that was why the burger meat business went away. And you’d be partially correct. Fred did sign up to be a cook in the Navy, but the horse burger business had fallen out of fashion starting in the late 30s as the country crawled out of the Great Depression.

Fred and Charles and Fred’s two younger brothers Morton and Peck had by this stage expanded their business into the disposal of all manner of unwanted animals, from roadkill removal to the catching and killing of stray cats and dogs. It’s hard to imagine now, but the United States in the late 30s and early 40s was being overrun by stray cats and dogs. Especially dogs. The number of small children mauled or just plain eaten by roving packs of wild (or untrained- I guess maybe stray is the better term) dogs had risen, in New Jersey at least, but also in Connecticut and coastal New Hampshire, to 1 in 5. 1 in 5 children mauled or eaten by dogs.

This was also a time when membership in the National Rifle Association grew at a tremendous pace, and the first concealed carry laws were passed, though more on the local township level, not nationally, and being more “ordinance” than law. As the number of fatalities associated with children being eaten or mauled by stray and wild dogs (some were legitimately wild, born under train tracks and never knowing the comfort of the masters hand) so too did the sales of handguns and portable rifles, and at first so did the number of injuries associated with poor marksmanship. Passerby or neighbors clipped or even killed by stray bullets fired at wild dogs or vicious tomcats.

Remarkably enough, this is also the same time when optometry became a household word in America, and when the eye care industry was first de-regulated, allowing for non medical doctors to make, manufacture and sell eyeglasses. The sale of eyeglasses, combined with the rise in NRA membership, and their associated firearm safety training classes, led to both a dramatic reduction in random accidental shootings and the dramatic decline of children mauled or wholly consumed by gangs of wild dogs. Also raccoons.

It truly must have been an amazing time to be alive in America. God, what I wouldn’t give to have lived back then.